Surviving to thriving: Transforming transport planning in times of crisis

9 December 2025

We live in an age of crisis: pandemics, climate change, cost-of-living pressures, global conflicts, and rapid technological disruption. For transport planners, these shocks pose an existential question: how is our work relevant in these times of crisis?

Author: Marie Landingin – VLC Senior Consultant (Transport Advisory)

A term that captures the current landscape is ‘polycrisis’. Coined in the 1990s, the term refers to a simultaneous collision of crises that are interlinked and reinforce each other. Polycrisis captures a global sentiment where 90% of people feel increasingly vulnerable to a growing number of crises (Ipsos, 2024). It’s a concept that is shaping thinking across climate, health, and governance, but is rarely applied to transport. Through this lens, our profession stands at three crossroads: knowledge, impact, and governance.

1. Knowledge: evidence in flux?

Transport planning depends on evidence. The base case is a key concept to capture the existing situation and is a critical benchmark for change (Infrastructure Australia, 2021). However, our “base cases” are becoming increasingly unreliable. COVID-19 upended commuting patterns. Extreme weather events erase infrastructure overnight. Solid assumptions are now fragile. Crises highlight the risk of justifying our efforts and investments in realities that may no longer exist.

To stay relevant, we must evolve how we collect and use knowledge. One suggestion may be disruptive digital tools such as artificial intelligence (AI), digital twins, and big data, which rapidly collect and analyse changing data. On AI alone, 2025 research from Jobs and Skills Australia suggests that 75% of firms in professional services and public sector (which includes transport planning) have less than half the depth of literacy in generative AI than half of the ICT industry.

This suggests that emerging skills are not (yet) well distributed in our profession nor keeping pace with other industries. Furthermore, inviting different perspectives, from generalists and those from non-traditional career pathways, can help bridge industry gaps and help us see what’s missing.

In times of crisis, when thinking about knowledge, we are invited to consider:

- As a transport profession, do we understand our collective pool of knowledge and skills, and our potential shortcomings/gaps?

- Do we truly invite diverse viewpoints – generalists, professionals with a non-traditional pathway – and enable them to meaningfully challenge our status quo?

- Are we sufficiently learning more, widely, and quickly?

2. Impact: whose future matters?

Crisis heightens urgency, chasing quick wins. This often glamorises shortcuts, making it easy to forget what is not top-of-mind. How are different groups impacted and are these impacts equally distributed? There are many dimensions to discuss this, but a critical perspective is present bias.

Present bias – our tendency to overvalue immediate benefits over long-term gains – shapes everything from personal choices to transport economics. Discount rates, for example, often undervalue long-term benefits like climate resilience in favour of immediate travel time savings.

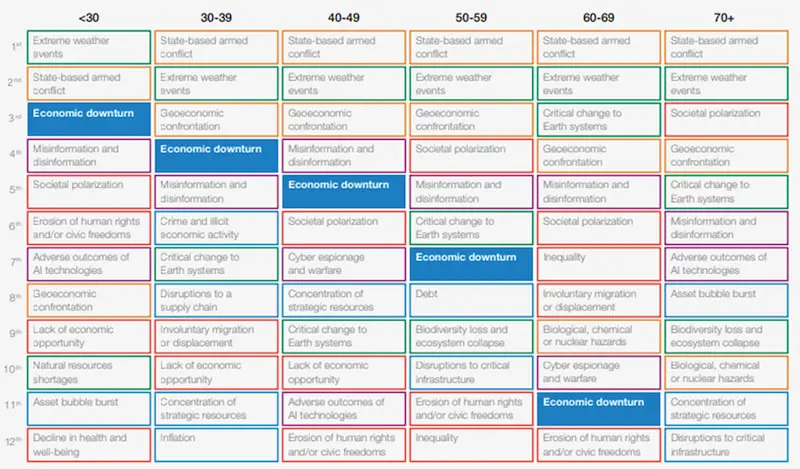

Present bias is the tendency for people to trade off potentially larger, long-term future rewards for more certain but typically lesser immediate or present rewards. However, what presently matters to you depends on a range of individual factors. For example, where you sit in life matters, with the World Economic Forum’s 2025 Global Risks Report suggesting a global generational divide between different age groups when it comes to the importance of different global issues. This analysis suggests that people worldwide under 30 years old rank economic downturn as their third biggest global concern. However, this priority drops the older we get, eventually not even in the top 12 priorities for people aged over 70.

Perception Survey 2024-2025)

In transport economics, discount rates can reinforce present bias. The discount rate is the critical tool for transport investment in economic analysis. The discount rate chosen reflects a judgement about the future value of costs and benefits associated with an investment or project. However, discount rates are widely debated in fields that seek to deliver long-term benefits, such as transport (OECD, 2011 and Grattan Institute, 2018) and climate (Stern, 2006). Some argue that current discounting practice heavily undervalues long-term benefits, such as climate resilience and mode shift — by prioritising more certain short-term benefits, such as travel time savings. Discounting is one example of how we may be systematically disadvantaging younger generations and generations that don’t yet exist.

In times of crisis, when thinking about bias and equity, we are invited to consider:

- Can we confidently say that our practice, processed, and preferred project options are unbiased?

- Have we transparently accounted for our biases in our evidence-based approaches?

- How can our current tools (e.g. discount rates or metrics) better represent long-term benefits?

- How do we support education, involve, and listen to young people’s demands?

- How do we mobilise society through good governance?

3. Governance: trust under pressure?

How do we reliably lead, decide, or support decision-makers in times of crisis? Governance is how a system functions, regulates, and makes decisions. This is arguably the most challenging and most important crossroads we face in times of crisis.

To make transport decisions, transport professionals have been trusted – often alongside public sector agencies – to deliver the needs of society. However, we operate in a contested space fostering public distrust. For instance, one study suggests that 97% of Australians want policies that look out for long-term interests for future generations (EveryGen, 2024). Meanwhile, the 2023 OECD Trust Survey suggests that only 43% of Australians believe that the Australian Public Service looks out for society’s long-term interests (OECD, 2025). A potential contributor to this is the fact that, out of 32 committed major transport projects valued over $500 million between 2016 and 2021, only eight had business cases that were publicly released (Terrill, 2021).

However, there is reportedly a greater, global trend of cynicism, social polarisation, and declining social trust and social cohesion. A 2024 study suggests that two-thirds of adults in Australia agree that “people do not know who they can trust and rely on” (Scanlon Institute, 2024). Such perceptions of social cohesion are worsened by those who identify as poor, unemployed, young, renters, and socioeconomically disadvantaged. This general sense of distrust in society makes it even more challenging to deliver societal outcomes, such as through transport infrastructure.

Potential solutions for such a challenging governance landscape may be to borrow the principles of ‘SMART 2.0 Governance’ (Okada & Renn, 2025). This approach suggests looking to small and solid, modest and multiple solutions, seeking to be adaptive, anticipatory, timely and transformative.

Being transformative is a critical call to action. For example, in 1999, the former bodies that are now Queensland’s Department of Transport and Main Roads collaboratively mapped four futures for Southeast Queensland in 2025. All eventuated in some way. The collaborative process helped shape integrated strategies in Queensland but dismissed deeper consideration of “speculative wildcards”. One “wildcard” was a world plague – which rang true with the COVID-19 pandemic. While they were not necessarily wrong, this is an example of how a polycrisis demands that we stretch our imagination further since speculative wildcards are always possible.

In times of crisis, when thinking about governance:

- Are we honouring our role as professionals serving the public interest?

- Are we courageous enough to collaboratively imagine speculative, disruptive futures?

- How do we use crisis as a springboard for transformative change?

Where to next?

Polycrisis thinking reminds us to see transport not in isolation but as part of a complex, interconnected world. It reminds us that change is inevitable, but not unmanageable.

As planners, we already have tools to navigate uncertainty. What is most needed now is courage: to embrace evolving knowledge, balance short-term and long-term impacts, and govern with transparency and trust.

Transport planning remains relevant in times of crisis – if we rise to the challenge. Crises are opportunities for transformative change. Change can be good, if we choose to make it so.

This article is adapted from presentations for the Transport Professionals Association, delivered at the 2025 National Transport Conference and for the Transport Modelling Network’s national webinar on ‘Widening the perspective of strategic modelling’.