Should we still survey households on their travel?

13 March 2018

Every waking hour, our smartphones are sending blips of data telling Google and our phone providers where we are and how quickly we’re moving. And each time we swipe our smart card as we hop on a bus or train, our transport planning agencies learn more about our travel patterns.

With all the travel data potentially for sale and at transport planners’ fingertips, do we still need to go and speak to people and ask them where and how they travel? We argue, yes.

This is exactly what the NSW Government has done every year since 1997 with its Household Travel Survey (HTS). Around 3,500 households are surveyed right across Greater Sydney in Australia’s most comprehensive and regular survey [1].

Even with the advent of computer tablets that can efficiently guide survey questioning, directly speaking to people still comes with a large price tag. And with more people living in secure apartment buildings, the face-to-face approach also tends to over-represent people with an accessible front door.

Government spending is always under scrutiny, so it’s no surprise that the promise of new data sources holds appeal. But do these new data sources cover everything that we get from HTS? And if not, are there ways of combining approaches to get the best of both worlds at lower cost?

The Household Travel Survey: a treasure trove

HTS interviewers ask household members a wide array of questions about their travel behaviours (and even their non-travel behaviours if they work from home). These responses are linked to the respondents’ home locations and a range of characteristics, such as income and car ownership.

From HTS responses we know exactly which travel mode someone uses. By contrast, mobile phone movement data requires an informed guess, based on travel speeds and other attributes. This ‘imputation’ of travel mode is fairly accurate using algorithms [2].

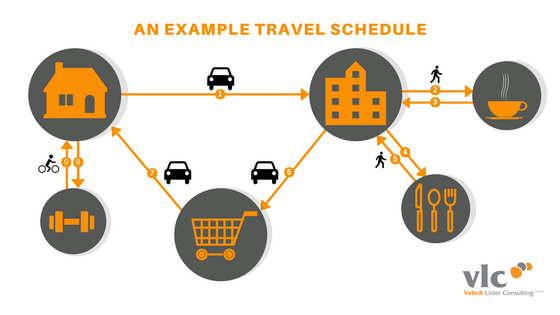

The HTS also finds out why people are travelling and where exactly they are going. This is much more difficult to impute by observing our movements. We might go from home to a tall building in the city, but there could be a doctor’s surgery, lawyer’s office and department store in the same building. Were we shopping, going to a medical appointment, or commuting to work?

But it is the linking of travel behaviour to household characteristics that sets HTS even further apart from newer forms of travel data. Without revealing and cross-referencing a range of confidential customer information, it would be difficult to establish even half of the HTS characteristics in mobile phone, Google or card payment data.

Travel models: powerful yet hungry beasts

All of the rich travel and household characteristic data gathered by HTS is a fundamental input to transport planning. If we want to understand the impacts of a future rail line or motorway in our cities we need to first understand how different travellers make use of transport infrastructure and services already. How do different people trade off the faster journeys against having to pay a toll, and who is more likely to drive rather than taking the train over the same distance?

Over several decades, transport planners have developed mathematical models that summarise our travel behaviour in response to the many options we have in our daily lives. These powerful models are currently estimated based on HTS data. Critically, these models rely on being able to identify behavioural similarities among types of households and individuals as well as the types of trips they are taking. For instance, travellers who own a car are more likely to make a shopping trip to a more distant location than a person without a car. Yet that same person may travel by bus when they are going to work. To understand future travel behaviour in total, we ‘simply’ need to be able to forecast the number of each different household types and activity types across the city.

More recently the emergence of technology-enabled business models (e.g. ride-sharing and home deliveries) and policy options (e.g. road pricing) have pushed the limits of existing models. New models, if anything, are likely to require even more detail on household characteristics. For example, we may want to understand how the members of a single-car household negotiated their different activities and trips over the course of the day. To estimate such a model, we would need a lot more insight than we would get from simple location observations of each person through the day.

Possible ways forward

Arguably there is value in shifting to a national approach to surveying households about their travel. This would promote consistency and potentially reduce the funding volatility inherent in a state-by-state approach. In some jurisdictions, travel models rely on surveys from the late 1990s, right at the start of the internet age.

Whatever the funding approach, it is clear that there are opportunities to improve data collection to harness new technologies. A blended approach could use a tailored smartphone app for most respondents, with in-person survey for households without smartphones. Such an app would request demographic data input and would automatically track travel via GPS. This system could prove to be a win-win, since the cost of collection would be much reduced and response rates could be boosted by small payments to respondents.

Conclusion

Infrastructure Australia recently highlighted the stark planning options we must face with massive urban population growth projected across the country [3]. We should not fly into these decisions blindly. National dialogue is essential and should be informed by modelling of the implications of pursuing different options.

Understanding how different parts of the population will respond to proposed infrastructure investments and policies is central to assessing the likely success of alternative planning decisions. Detailed household travel data offers dramatically greater insights into the travel behaviours of different groups than emerging data sources. So finding new and financially sustainable ways to collect household travel data is critical for us and other planners to continue to develop tools to inform dialogue and planning for the coming decades.

Disclosure: Veitch Lister Consulting develops travel models for major cities in Australia and is therefore a current user of HTS data.

Daniel Veryard leads VLC’s transport advisory business in NSW; Tim Veitch is VLC’s Chief Executive Officer and developed VLC’s Zenith travel models.

Footnotes

[1] Li Shen, Sherri Fields, Peter Stopher and Yun Zhang, 2016, “The Future Direction of Household Travel Surveys Methods in Australia,” Australasian Transport Research Forum 2016 Proceedings

[2] Li Shen and Peter Stopher, 2014, “Review of GPS Travel Survey and GPS Data-Processing Methods,” Transport Reviews, Volume 34, Issue 3, pages 316-334

[3] Infrastructure Australia, 2018, “Future Cities: Planning for our growing population,” Infrastructure Australia’s Reform Series, available: http://infrastructureaustralia.gov.au/policy-publications/publications/future-cities.aspx